Secure Women, Secure States

In a 2008 survey by Global Rights and Partners for Justice, 87 percent of Afghan women respondents reported that they had been abused, almost all by intimate family members, particularly husbands. Afghanistan is also a highly unstable nation, ranking seventh in the world on the Fund for Peace’s Failed States Index and last on the Global Peace Index. Is this a coincidence?

Most agree that an unstable, warring nation is likely to produce stressed, traumatized households. But the causal arrow may also point in the opposite direction. When a society normalizes violence and oppression between men and women, the two halves of humanity in households and communities, effects may be felt nationally.

Academic research has investigated the possibility that the security of women and the security of the nation-state are integrally linked.

In “Gender Equality and State Aggression: The Impact of Domestic Gender Equality on State First Use of Force,” Mary Caprioli indicates that states with higher levels of social, economic, and political gender equality are less likely to rely on military force to settle disputes.

Caprioli and Mark Boyer, in “Gender, Violence, and International Crisis,” show that states exhibiting high levels of gender equality also exhibit lower levels of violence in international crises and militarized inter-state disputes.

In “Gender Equality and Intrastate Armed Conflict,” Erik Melander has replicated these results, finding virtually the same pattern with respect to intrastate incidents of conflict.

Caprioli and Peter Trumbore in “Human Rights Rogues in Interstate Disputes” find that states characterized by gender and ethnic inequality as well as human rights abuses are more likely to become involved in militarized and violent interstate disputes, to be the aggressors, and to rely on force when involved.

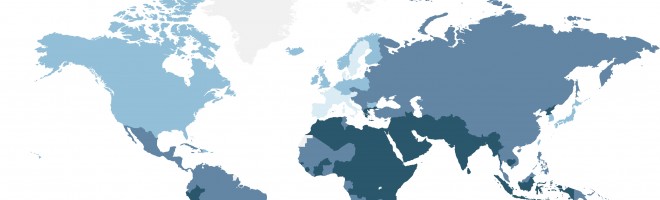

My colleagues and I at the WomanStats Project extended this examination of the connection between the status of women and peace. In a series of empirical analyses over 140 nation-states, we found that the overall level of violence against women was a better predictor of state peacefulness, compliance with international treaty obligations, and relations with neighboring countries than indicators measuring the level of democracy, level of wealth, and civilizational identity of the state. In ancillary analyses, we also found that polygyny was a risk factor for state instability and that nations with discriminatory family laws had higher levels of violence against women. We are currently in the process of demonstrating the relationship between marriage customs, systems of political governance, and indicators of state instability.

Now that the empirical picture has become clearer, we can ask why these associations hold and look at what implications they have for policy making. That the associations are so robust tells us something important already: The treatment of women in a society is a real barometer of the degree to which a society is capable of peace.

This is not because women are altruistic, peace-loving angels, for they are not— although, as Malcolm Potts and Thomas Hayden rightly remark in their book, Sex and War: How Biology Explains Warfare and Terrorism and Offers a Path to a Safer World, “Women have never shared men’s propensity to band together spontaneously and sally forth to viciously attack their neighbors.” The reason the associations between violence against women and general stability of a nation hold is because how the two different but interdependent halves of humanity live together in a society tells us how that society copes with difference and conflict arising from that difference. The difference between sexes is usually the first difference encountered in life because it is manifested in one’s own parents. If a society’s culture suggests that sexual difference is handled by male interests trumping female interests and that conflict is resolved through violence, protected by group-sanctioned impunity, this becomes the template within that society for dealing with all differences— ethnic, religious, cultural, and ideological. If violent subordination is the norm in nearly every household, how can the state ever be stable or at peace?

A policy implication of the research findings regarding the link between gender equity and state security is the empowerment of women and girls. If society rejects impunity for violence against women and champions equal voice and equal representation for women in all important decision making, from the home to the state, these old, dysfunctional templates will crumble. The security of women influences the security of states in a way that we, as a world, must finally recognize and act upon. Just as former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton asserted that the subjugation of women is a direct threat to the security of the United States, so the world must develop its own Hillary Doctrine, or pay the price in national and international insecurity.