She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World

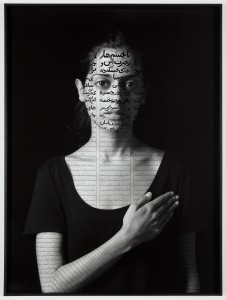

Copyright Shirin Neshat, Courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Over the past decade, and particularly since September 11, 2001, exhibition organizers, art critics, and the international market have paid more attention to contemporary art from Iran and the Arab world. A variety of cultural initiatives has brought about this change, but it is also an effect of the growing political turmoil in the region. One of the most significant developments is the increasingly important role of women photographers, whose remarkable and provocative work is challenging stereotypes and providing alternative images of the region from those that we are inundated with in the media.

She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World, at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, was the first major North American exhibition of this exceptional photography, introducing the pioneering work of twelve leading contemporary Arab and Iranian women photographers. The exhibition and accompanying book highlight the rich variety of artistic expression and diversity of approaches the photographers have taken to portraying their native lands. As notions of international, national, and personal identity—and in some cases the countries themselves—are being dismantled and rebuilt, the photography reflects the complexities of a region undergoing unparalleled change, balancing its contradictions while challenging stereotypes and addressing social and political issues.

Metro #7

Rana El Nemr (born in 1974)

2003 | Chromogenic print

Reproduced with permission.

Courtesy of the artist

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In Arabic, the word rawiya means “she who tells a story,” which is also the name of a recently founded small collective of female photographers based in the Middle East (Iranian Newsha Tavakolian and Jordanian Tanya Habjouqa, both included in the exhibition, are founding members of Rawiya). The photographs in the exhibition are themselves a collection of compelling narratives about contemporary life. They pose questions about concepts of identities and the ways they can be layered, constructed, fragmented, and staged, as the artists reflect on the power of politics and the legacy of war. The photographers explore the visible and the invisible, notions of voice and language, the permissible and the forbidden, and the coexistence of life and war. Ranging in style from fine art to photojournalism, the images offer insight into major political and social issues in a part of the world that is historically misrepresented and often misunderstood.

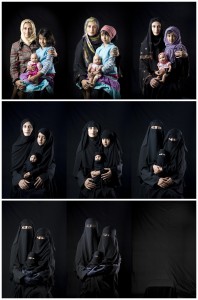

© Boushra Almutawakel

Courtesy of the artist and East Wing Contemporary Gallery

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

On women artists in Iran in “Contemporary Art in the Middle East,” Lebanese-Iranian freelance curator and gallery owner Rose Issa points out a paradox regarding perceptions of the country: “Iran, the same country that supposedly represses women, can also produce [women directors such as] Samira Makhmalbaf, Rakhshan Bani Etemad, Mania Akbari, and Forough Farrokhzad.” She also highlights some of the young women photographers today who have overcome perceived obstacles to working in Iran. Iranian-born professor and author Hamid Naficy also discusses the emergence of particularly strong women film directors from Iran in recent decades. In “Poetics and Politics of Veil, Voice, and Vision in Iranian Post- Revolutionary Cinema,” Naficy states, “The rise of differently situated women directors is emblematic and constitutive of the forceful emergence of women into the public space in many spheres, including politics, cinema, tele- vision, press and performing and visual arts.”

In her book Art Press, Omid Rouhani comments that after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iranian women artists “began looking for ways of proving and expressing their identity, and did so well before men. This autobiographical, personal vision of collective social and individual issues, both existential and philosophical, was more prominent in work by women. And in this regard a new phase began with the presidential elections of June 2009: beyond questions of self-discovery, feminism and equality, new issues await today’s women artists.” Women have frequently been at the heart of, or very active in, social change, as seen in the recent protests in Iran and the Arab world.

Newsha Tavakolian, born and based in Tehran, feels significantly empowered as a female photographer and as an Iranian woman. “When you see me at my work,” she said in a 2012 interview, “I always wear long, long abaya and my hijab because then I have power that way.” Even as the government requires women to wear a hijab in public, women such as Tavakolian use the covering to wield more autonomy and agency.

While the majority of photographers in this exhibition do not wish to be categorized solely as women photographers, several recognize that their experiences differ from those of their male counterparts. Egyptian photographers Rana El Nemr and Nermine Hammam refer to being in privileged positions as women. As Hammam stated in a 2012 interview, “Gender comes into play in the way people respond to me as a female photographer.” She suggests that in her series Uppekha, the images would have been different if she had been a man because her subjects would have reacted differently to the experience of being photographed.

She Who Tells a Story seeks to use the photographers’ aesthetic as a tool to help understand the complexities of a region that are too often simplified. It is an invitation and opportunity for all, not only to discover new photography but also to shift perspectives and open a cultural dialogue.

Women of Gaza 3

Tanya Habjouqa (Jordanian, born in 1975)

2010 | Car on beach with family behind

© Tanya Habjouqa | Courtesy of the artist and East Wing Contemporary Gallery | Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston